This is an article from our monthly newsletter. Sign up to the mailing list. This article is from Sacred Footsteps and has been re-published with the permission of the author. You can read the original here.

The Dala’il al-Khayrat, a collection of prayers and blessings upon the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ has been recited in homes and zawiyas, mosques and maqams around the world ever since it was compiled in the 15th century.

The book, translated roughly as The Guide to Goodness, was composed by Shaykh Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Jazuli, a prominent scholar born in modern-day Morocco. It is reported that he compiled the book after a miraculous encounter with a young girl. The story states that Imam al Jazuli went to a well to make his ablutions, but was unable to draw any water. Upon seeing his predicament, a young girl came and spat into the well, at which point it over flowed with water. The Shaykh asked her how she had achieved such a high spiritual state, to which she responded, ”By saying the Blessings upon him whom beasts lovingly followed as he walked through the wilds (Allah bless him and give him peace).” On hearing this, he decided to compile his Dala’il al-Khayrat.

Alongside recitations of the book, which take place daily all over the world, including at the tomb of Imam Jazuli himself in Marrakesh, a beautiful tradition of illuminated and illustrated manuscripts of the Dala’il al-Khayrat emerged from Morocco in the west all the way to China in the east. It became one of the most copied religious texts in Sunni Islam after the Qur’an.

A common theme among them are representations of places and objects related to the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, including illustrations of Mecca and Madina.

Birds-Eye View

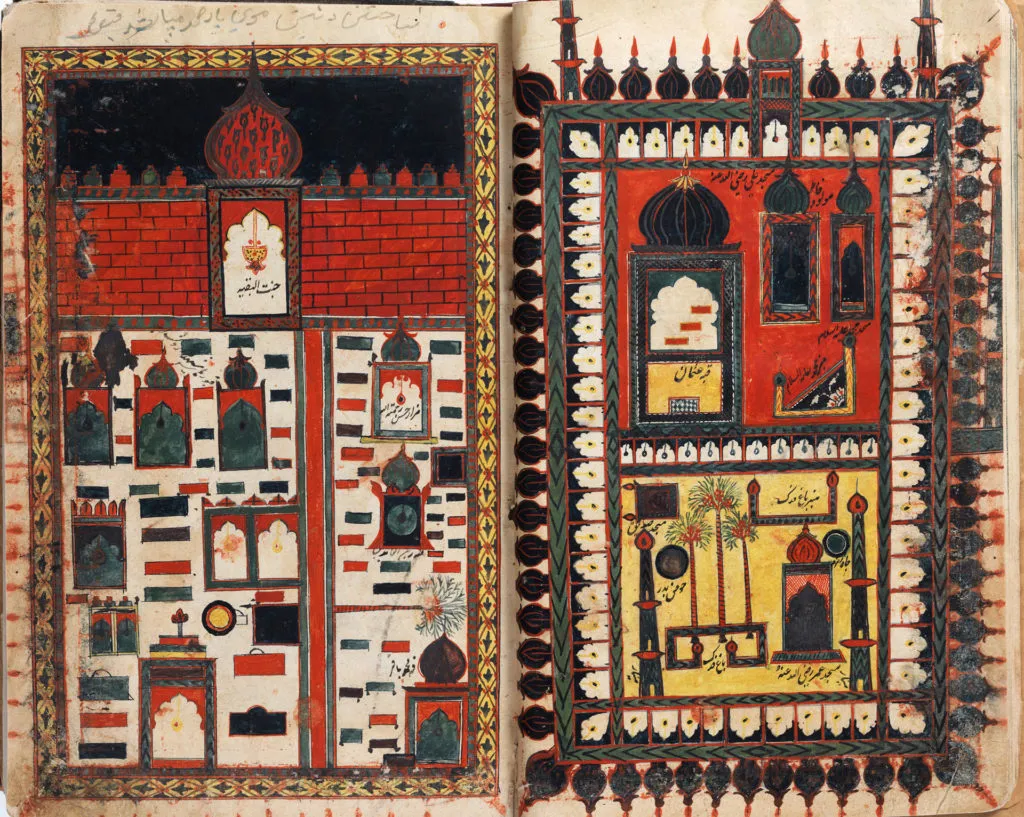

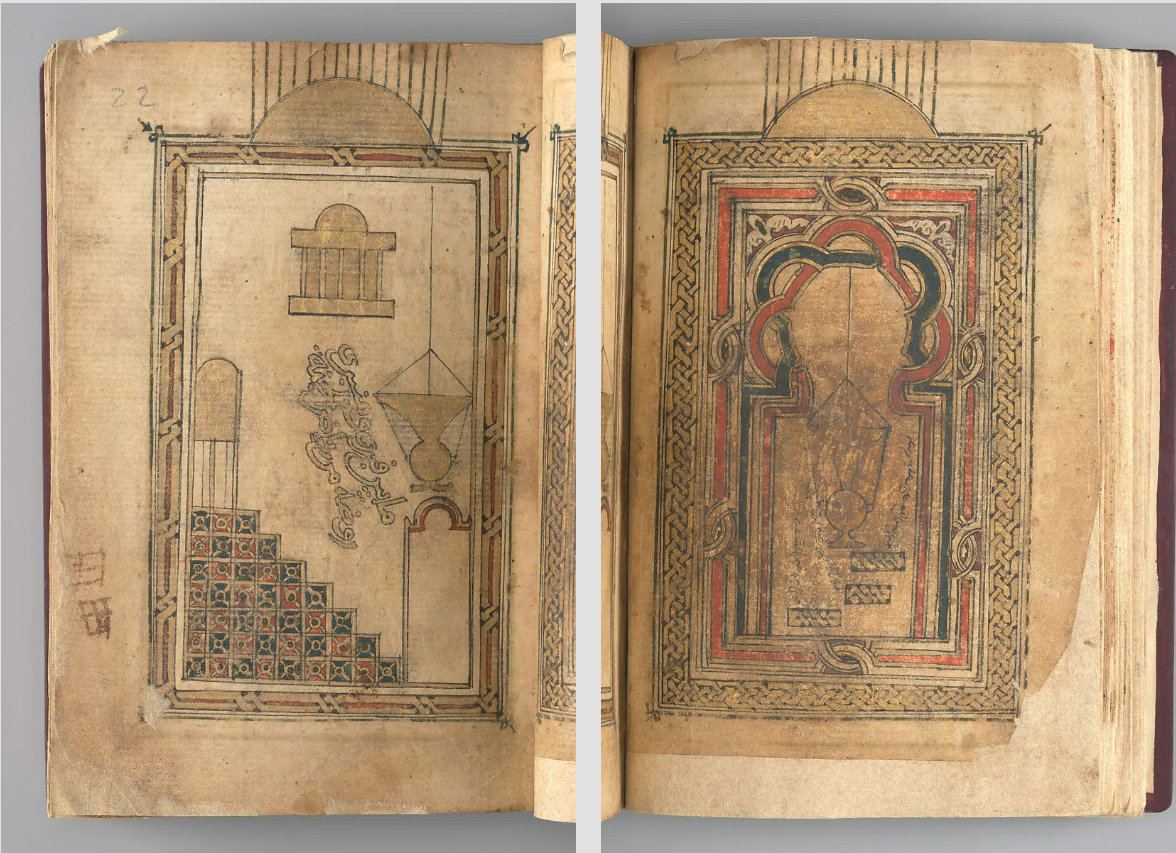

Below is a typical double-page spread, variations of which are found in numerous manuscripts. A birds-eye view of Mecca is depicted on the right; Kaba is visible, surrounded by the stations of the four madhabs, that once stood in the harem. On the left, the three rectangular shapes, represent the blessed resting places of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, and his Companions Abu Bakr and Umar al-Khattab (God be pleased with them) in Madina. The minbar of the Prophet is also visible.

Morocco. 16th century

The square format of this manuscript, along with the Maghribi script and late Western Islamic style of decoration found throughout, point toward the manuscript being produced in 16th century Morocco. But typically of Islamic manuscripts, it is a witness to the vast tradition of pilgrimage and travel in the Islamic world. The manuscript was acquired in a bazaar in Kabul, Afghanistan in the 1960s. The Devangri script on paper re-used to bind the manuscript, suggests that it had been taken to Mecca, where it was then acquired by another pilgrim from India1.

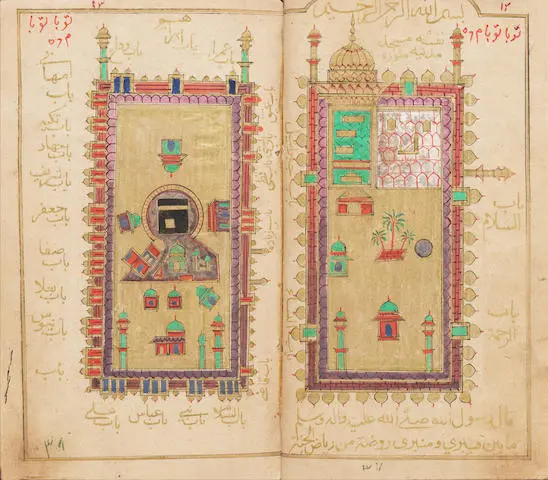

This 17th century manuscript, probably from Tunisia, is one of the earliest dated copies of the Dala’il al-Khayrat. Illustrated by the Muhammad bin Ahmad bin ‘Abd Al-Rahman Al-Riyahi, Mecca is again depicted on the right, Medina on the left. The minbars of both Holy Mosques can be seen in red on the lower halves of both pages. The three blessed tombs in Madina, though faded, can be seen within the square enclosure.

Double page depicting the Holy Sanctuaries in Mecca and Medina, from a Dala’il al-Khayrat manuscript, dated 1629-30. Probably Tunisia. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Friends of Islamic Art Gifts, 2017 (2017.301).

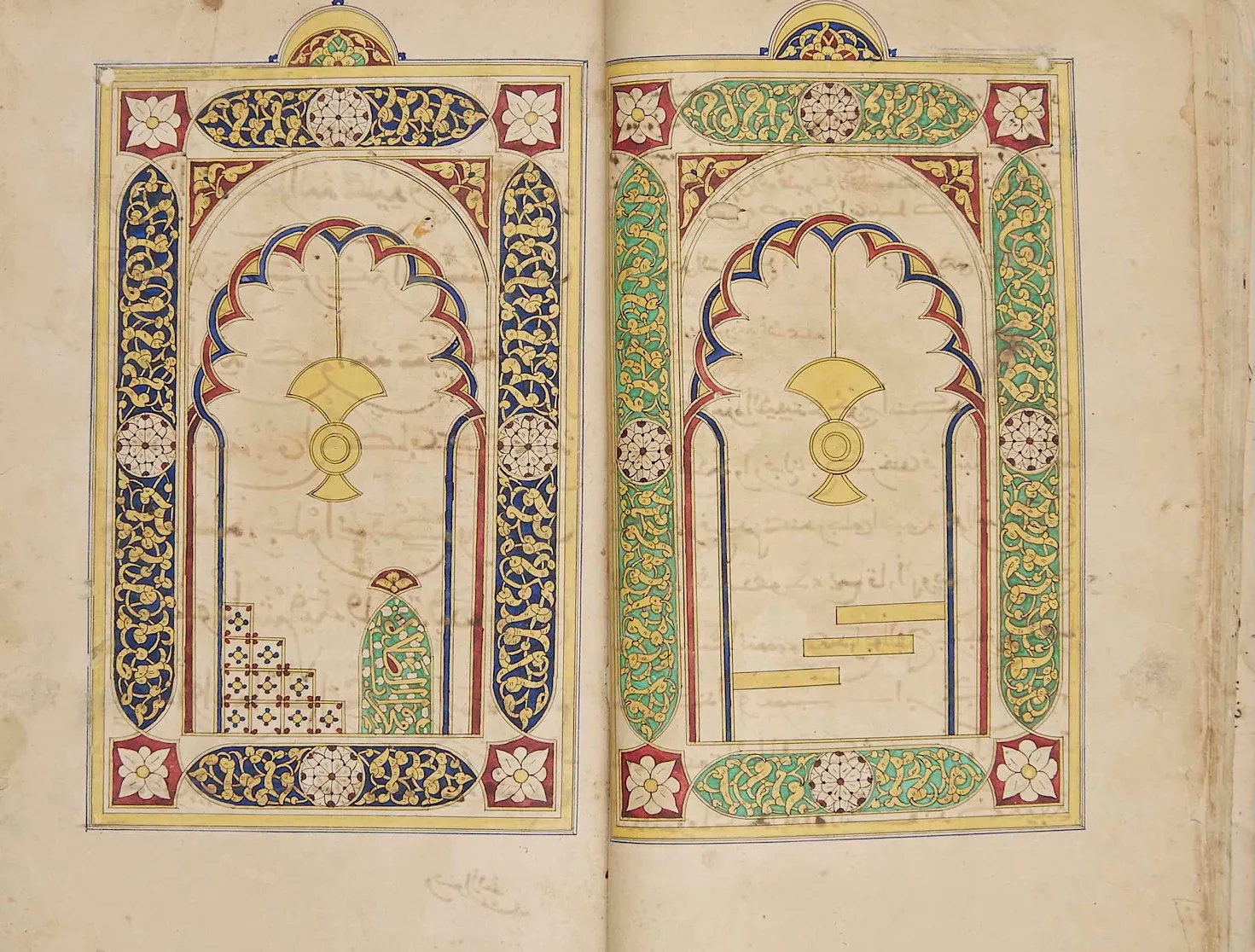

The three manuscripts below were produced in Kashmir, in the 19th century. They follow a similar format to the North African illustrations. The weeping date-palm is depicted on the bottom left of all three manuscripts. The third manuscript names Khan Yunus Khan Bahu as the scribe, and gives the precise date of its production as Sha’ban 1223 AH (September 1808 AD).

Double page depicting the Holy Sanctuaries in Mecca and Medina. Kashmir, c. 1800.

Double page depicting the Holy Sanctuaries in Mecca and Medina. Kashmir. Dated 19th century.

Double page depicting the Holy Sanctuaries in Mecca and Medina. Kashmir. Dated 1808/1223 AH.

This distinctive 19th century manuscript shows the Mosque of the Prophet on the right, and Jannat al-Baqi cemetery on the left. The prominent tombs are marked. It was produced possibly in India, or in Mecca by Indian artists.

Double page depicting the Holy Sanctuaries in Mecca and Medina. India, or possibly Mecca by Indian artists. Dated Rajab 1216 (November 1801) & Ramadan 1216 (January 1802).

This double page, taken from an Indian manuscript, has all of the doors of the mosques marked around the edges.

Double page depicting the Holy Sanctuaries in Mecca and Medina. India, probably the Deccan, early 19th Century.

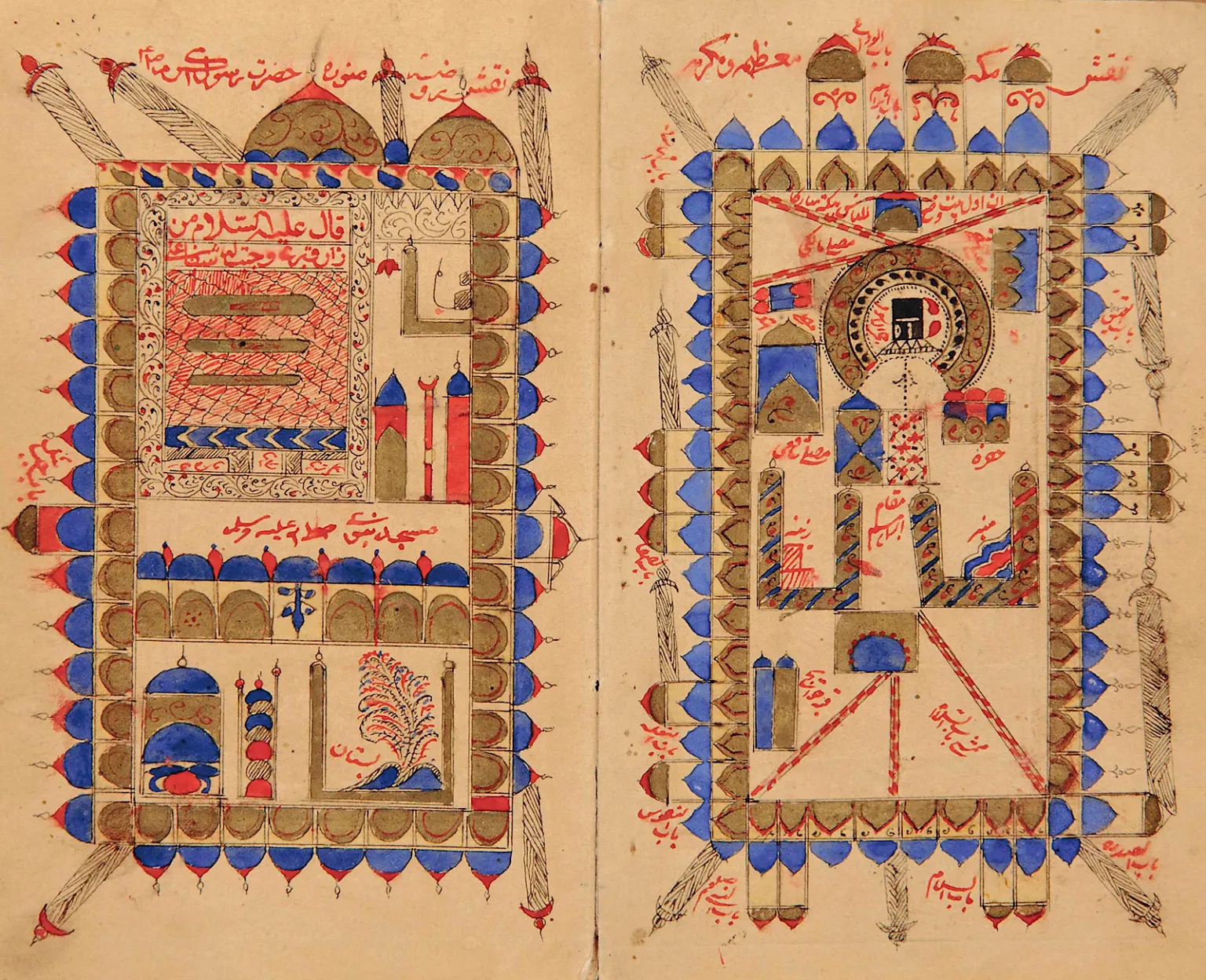

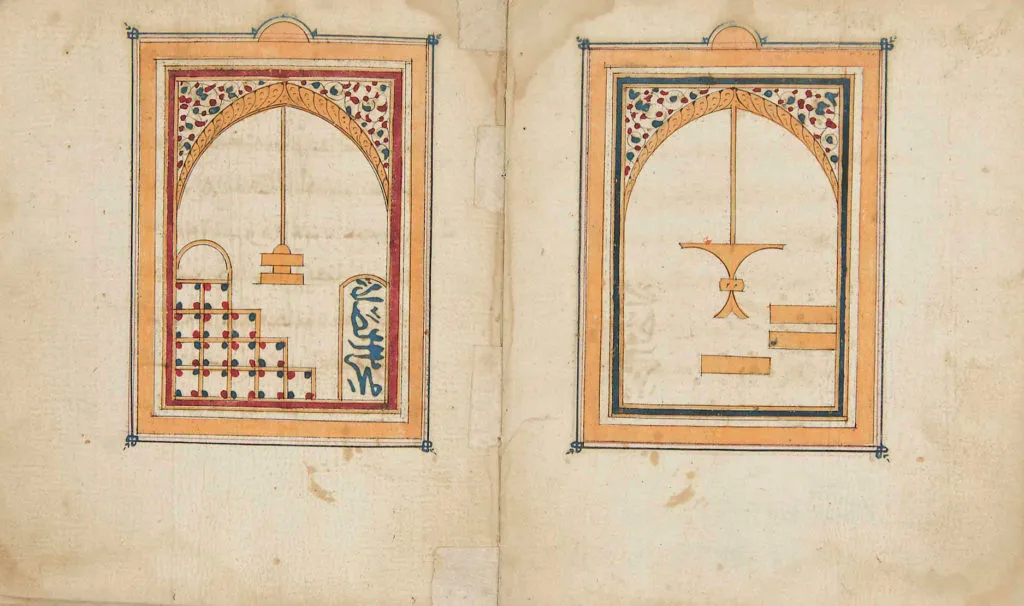

The illustrations below were produced in either 19th century Iran or Afghanistan.

Double page depicting the Holy Sanctuaries in Mecca and Medina. Ottoman Turkey, possibly Istanbul. Dated 1848-9/1265 AH. Khalili Collection

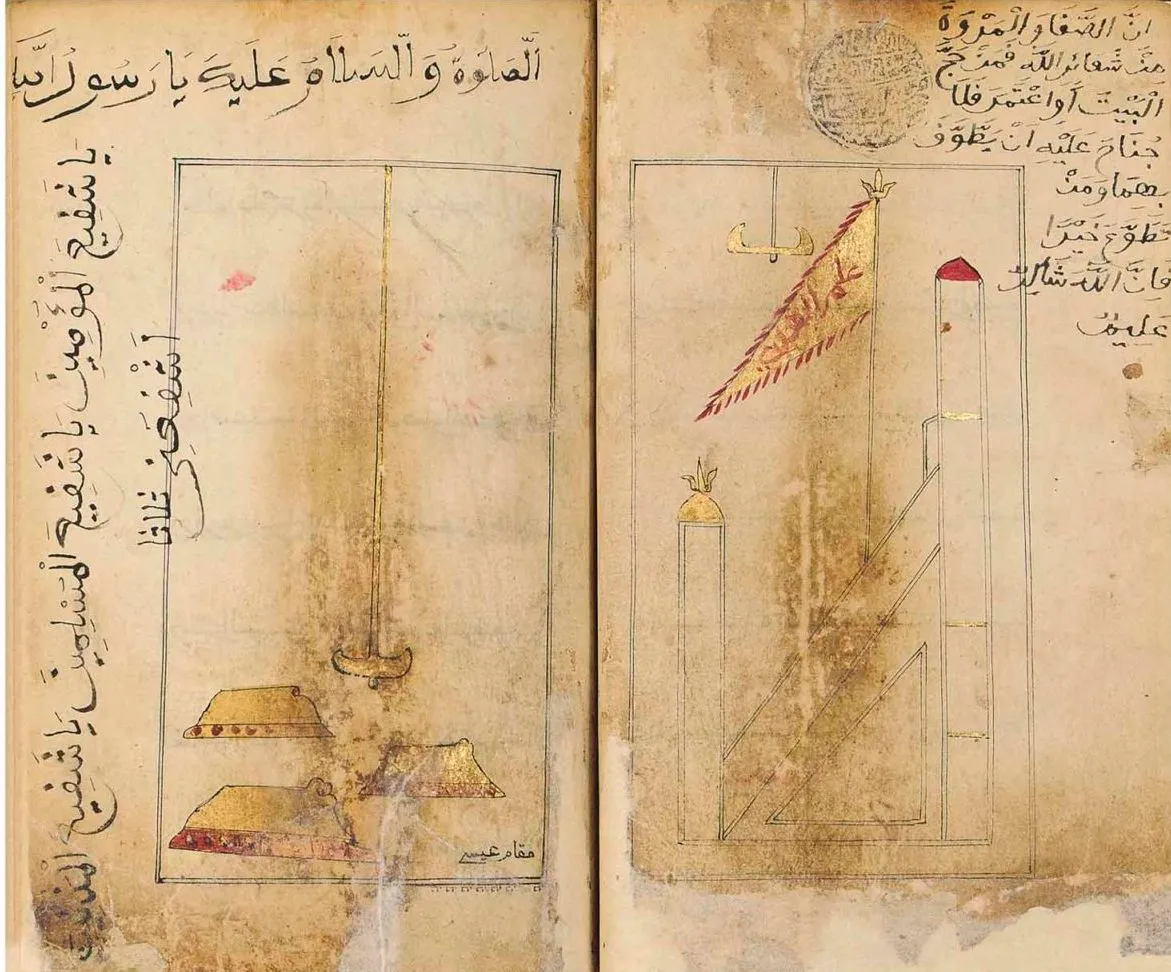

The Rawdah and Minbar of the Prophet

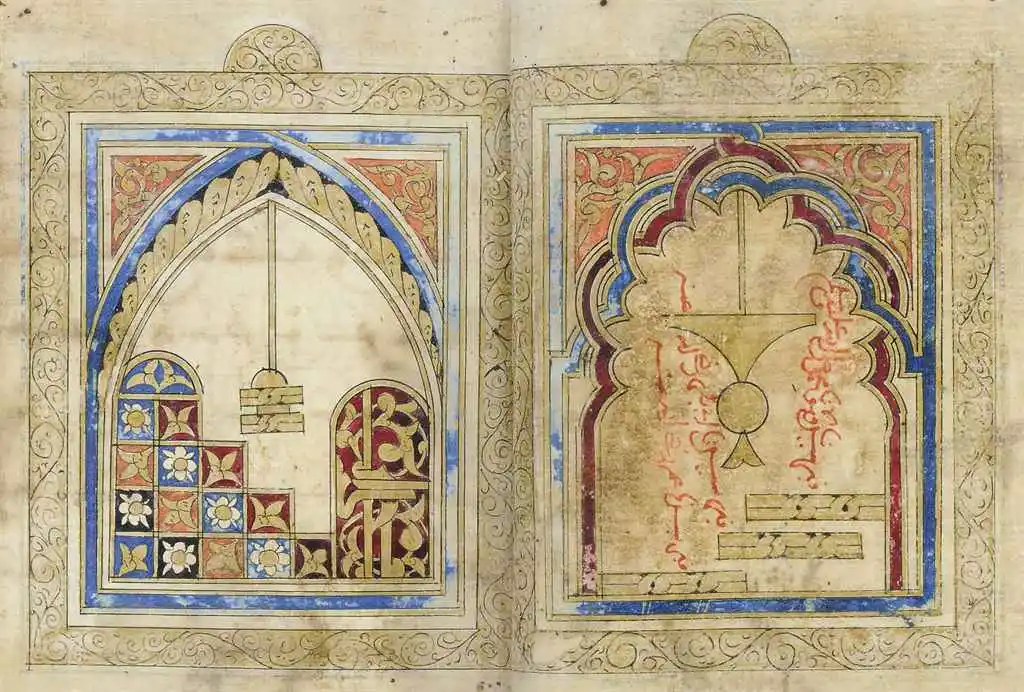

Dala’il al-Khayrat manuscripts also commonly contain a double page spread depicting the tombs of the Prophet ﷺ, Abu Bakr and Omar on one side, and the minbar of the Prophet on the other. The manuscript below is from 18th century East Turkestan. The final four are from North Africa.

East Turkestan. Dated 1719-20/1132 AH

Dated 1629-30. Probably Tunisia. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Friends of Islamic Art Gifts, 2017 (2017.301).

Morocco. Dated Sunday 23 Jumada 1303 AH/27 February 1886 AD.

Morocco. Before 1717-18/1129 AH.

Morocco. 16th century.

It is worth noting that in the centuries before the invention of the camera, illustrations such as the ones seen in the manuscripts of Dala’il al-Khayrat, were the only way many, many Muslims would ever see the Holy Cities and Mosques of Mecca and Madina, and the blessed tombs of the Prophet ﷺ and his Companions.

Though the representations are generally stylised and symbolic, they still often convey the architectural features of their time. The domed structures shown on the prominent tombs of Jannat al-Baqi cemetery, the stations of the four madhabs in the harem of Mecca, and general layout of the mosques, all no longer exist, or in the case of the latter, have been expanded beyond recognition.

But as with the actual text of the Dala’il al-Khayrat, which was adopted around the world purely out of love and longing for God’s Messenger ﷺ (its author even recited it at the tomb of the Prophet daily during his time in Madina), the illustrations too, depicted that which was a reminder of him, earthly traces of his existence and symbols of his presence- recognisable everywhere, from Morocco in the west to China in east.

Footnotes

[1] Sheila S. Blair and Jonathan M. Bloom, The Art and Architecture of Islam (1250-1800) , Yale University Press, 1995, p.263.